Using ARPA Funds to Address Equity in Science Education

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, students and teachers alike have shown incredible resilience as they worked to overcome unprecedented disruptions to their daily lives. For students traditionally under-served in education, these disruptions often extended beyond the school closures, exasperating existing inequities in their education and disproportionally affecting the communities they call home. Now, as schools across the U.S. chart their pathways forward, an influx of funding is providing a rare opportunity for schools to transform the educational experiences of our nation’s most vulnerable students.

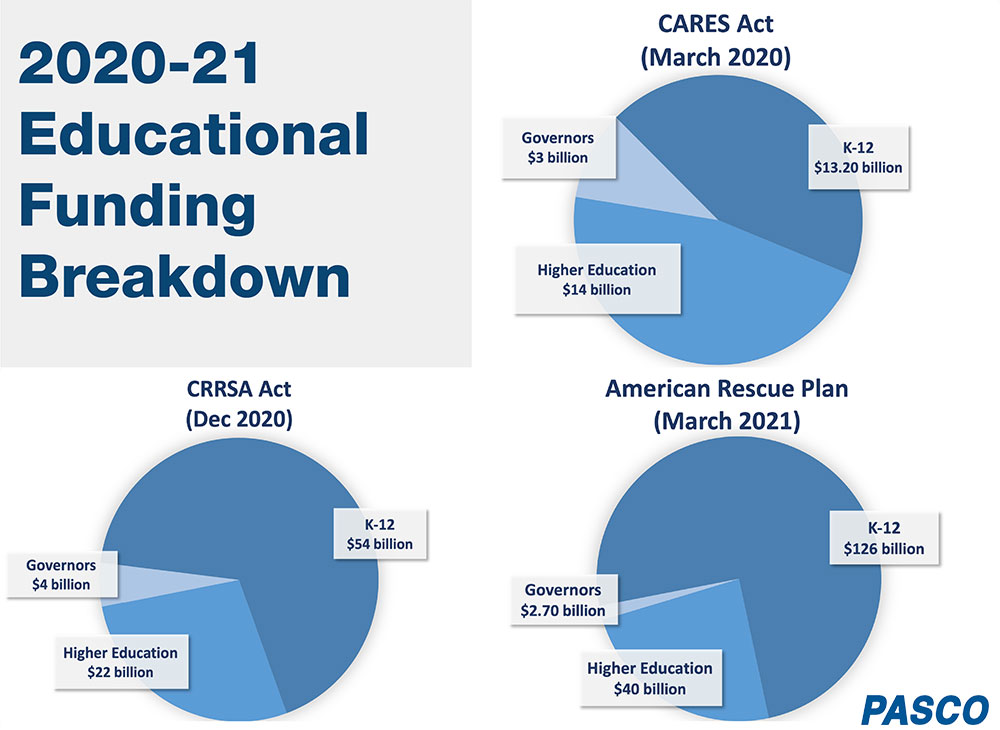

Since March 2020, the U.S. Department of Education has made more than $200 billion in stimulus funds available to schools, colleges, and universities through the CARES, CERRSA, and American Rescue Plan Acts. A significant portion of these funds were allocated to the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER Fund), which is comprised of ESSER I, ESSER II, and ARP ESSSER (ESSER III).

While the ESSER I and ESSER II funds were designed to help schools maintain services, improve safety, and retain faculty, the ARP ESSER funds established three State-level reservations “for activities and interventions that respond to students’ academic, social, and emotional needs and address the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on underrepresented student subgroups.” With such requirements established and an unusual abundance of funding, it is imperative that school leaders harness this opportunity by adopting evidence-based solutions capable of advancing equity and inclusiveness in their schools.

Compounding Inequities for Traditionally Disadvantaged Students

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, students of color, students from low-income backgrounds, and students in rural areas faced significant adversity in both their academic and home lives. For many, the pandemic was more than a disruptive shift to Zoom classes; It was an abrupt withdrawal of the resources they depended on.

As schools shuttered, inequities grew, leaving thousands of students across the U.S. without reliable access to technology, warm meals, or a quiet place to study. Without Internet or educational technology, these students struggled to attend classes, complete homework, and submit assignments. At home, their academic challenges were often compounded by the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on their communities. Whether it be the loss of a parent, reductions in parental income, or a sudden need for childcare, students across the nation suddenly found themselves navigating new roles at home that left limited time for learning.

As they decide how to spend ARPA funds, schools should reflect on the local challenges affecting their students and consider implementing evidence-based solutions that will empower traditionally disadvantaged learners to tap into their full potential.

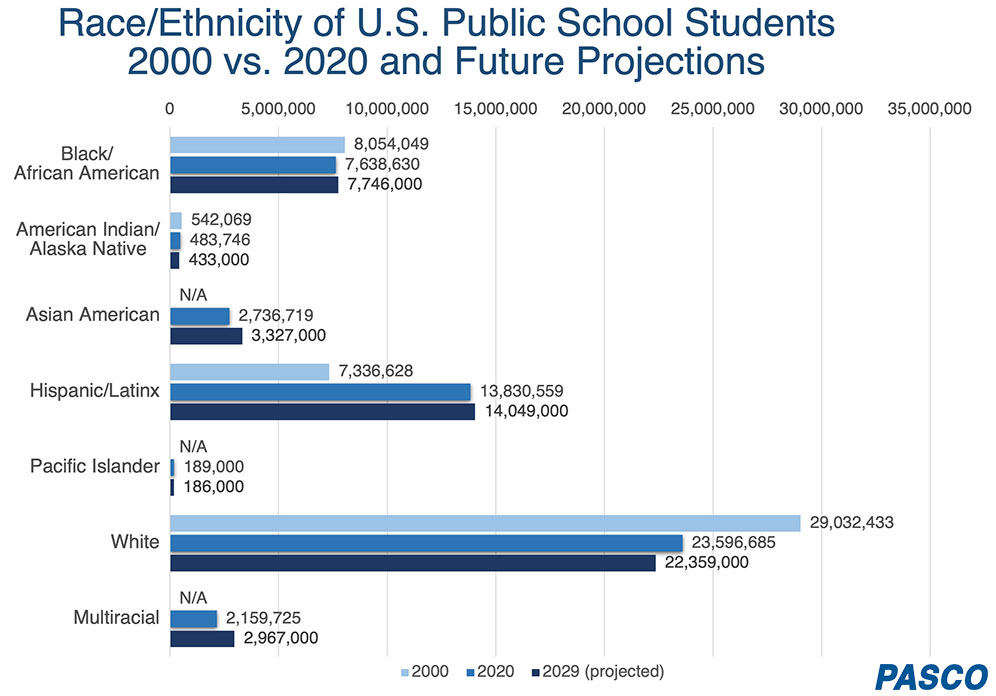

Systematic Inequities and Increasing Diversity in U.S. Public Schools

Even with proper funding, advancing the state of equity in our classrooms and communities is a monumental task. It’s no secret that the U.S. education system sits atop a foundation of systematic inequities, most of which are outside the control of school leaders. Nonetheless, the American school system’s role in shaping the competencies, skills, and perspectives of our developing citizens is unparalleled. As student populations become more racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse, schools must take a holistic approach to equity and reassess what they know about culture, language, and learning.

Evidence-Based Approaches for a More Equitable Education

Research has identified several pedagogical approaches with the potential to positively impact equity and achievement for all students in science and STEM education. While these teaching practices do contribute to creating a more equitable learning environment, truly transforming equity in science education demands a holistic approach. It is an enduring commitment to strengthening student-teacher relationships, improving cultural understanding, and providing equitable rigor – all of which must be sustained today, tomorrow, and every day forward.

Acknowledge and Address Implicit Bias

Taking a holistic approach to equity means that adopting equitable teaching practices is just part of the solution. The approaches within this blog will have limited success if the educator practicing them is unaware of their own implicit bias. Implicit bias pertains to the way in which attitudes or stereotypes affect a person’s perspective, interactions, and decisions in an unconscious manner.

Examples of implicit bias include misinterpreting the tone, meaning, or emotion behind a diverse student’s question or comment; having unfounded expectations for students based on race, gender, or income; and disproportionally reprimanding behaviors as a result of a student’s race, gender, or socioeconomic status. There are many helpful guides for educators looking to assess and address their personal biases, many of which are written by educators of color and advocates of equitable teaching practices.

Culturally Responsive Teaching

Culturally responsive teaching has proven to be an effective pedagogical approach throughout all levels of education. Often conflated with multicultural teaching, culturally responsive teaching aims to develop the cognitive capacities of under-served students in education by validating their experiences, valuing their perspectives, and tapping into their cultural learning processes.

On a foundational level, a culturally responsive classroom creates a learning environment where diverse students feel safe, valued, and welcome. Unsurprisingly, research has shown that healthy relationships between students and teachers can increase both student engagement and academic achievement. By using culturally relevant pedagogy, educators can develop a more equitable and inclusive classroom that encourages participation, communication, and collaboration among diverse students, their teachers and classmates. Developing this sense of trust is especially important for teachers who serve communities outside their own, as they are less likely to be familiar with their students’ culture and surroundings.

Culturally responsive teaching is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Rather, it relies on a teacher’s ability to validate and utilize the experiences, environments, and cultural backgrounds of their diverse students to drive knowledge development. Thus, there are numerous ways to implement culturally responsive teaching, many of which are included within the suggested reading materials provided at the end of this section.

One example of a culturally responsive teaching approach makes use of the oral traditions practiced by non-Western cultures. Many diverse students come from cultures with a rich history of oral traditions, meaning knowledge is shared and recalled through active communication. African American, Latinx, and Southeast Asian cultures are just a few examples of cultures that have historically used songs, poems, and rhymes to effectively share and recall knowledge. This is the same process used by math teachers, who will often teach the quadratic formula to the tune of “Pop Goes the Weasel” to assist with students’ memorization. Not only is this approach effective for all students, but it actually activates different regions in the brain’s memory systems that make it easier for students to recall the information later (compared to lecture-focused teaching).

Culturally Responsive Teaching vs. Multicultural Teaching Practices

It is important to note that while multicultural education and social justice education are designed to encourage cultural understanding and social awareness, culturally responsive education aims to develop the cognitive capacities of students traditionally marginalized in education. In other words, discussing social issues and raising awareness in the classroom may promote social harmony and cultural understanding, but these actions do not directly benefit the cognitive capacities of the very students they are intended to uplift.

Participatory Learning (Hands-on Inquiry)

Participatory learning aims to develop students’ science content knowledge and sense of agency by engaging them in authentic and collaborative scientific inquiry. Rather than memorizing facts as presented by their teacher, participatory learning invites students to shape their educational experiences by asking questions, collecting data, analyzing results, and communicating their findings with others. It can take many forms, often incorporating project-based activities, problem-based learning, as well as engineering and design principles that enable students to find meaning and purpose in their work.

As students pursue their own questions, investigations, and designs, they encounter gaps in their knowledge, which in turn leads to peer-to-peer problem-solving and collaboration. Throughout these collaborative, hands-on experiences, students routinely assess, adjust, and refine their knowledge as new information arises – a skill considered necessary for the ever-evolving future of work. Research has demonstrated the positive effects of such collaboration and group problem-solving on student competencies, indicating that students who participate in these collaborative participatory activities are likely to build understandings that extend beyond the understandings either student had individually.

Because participatory learning environments permit student agency and collaboration, they are considerably more equitable than traditional lecture-focused classrooms. During participatory learning, students exchange experiences, perspectives, and knowledge with peers as they strive to construct working knowledge about a concept, problem, or solution. Not only does collaboration strengthen students’ sense of community, but it also fosters empathy, cultural awareness, and a deeper understanding of authentic scientific practices. Active participatory learning also lends itself to differentiated instruction, enabling students with dissimilar skill levels and interests to pursue personally meaningful inquiries in different, yet equitable ways.

Admittedly, some schools have had difficulty adopting participatory learning in years past, mainly due to insufficient resources and a lack of relevant pedagogical content knowledge. The ARPA funding has given U.S. schools unprecedented buying power to implement 1:1 technology access, source inquiry materials, and extend faculty’s pedagogical knowledge of authentic inquiry practices for effective and equitable science instruction.

Related Reading and References

The following list provides open access links (no pay wall) to some of the peer-reviewed articles and relevant literature cited within this blog article. Peer-reviewed articles are marked with a *.

Culturally Responsive Education/Teaching Practices

- A Metasynthesis of the Complementarity of Culturally Responsive and Inquiry-Based Science Education in K-12 Settings: Implications for Advancing Equitable Science Teaching and Learning* by Julie C. Brown (2017)

- Principles for Culturally Responsive Teaching by Brown University

- Empathy, Teacher Dispositions, and Preparation for Culturally Responsive Pedagogy* by Chezare A. Warren (2017)

- The Culturally Responsive Teacher by Villegas & Lucas (2007)

- Exploring Culturally Responsive Pedagogy: Teachers' Perspectives on Fostering Equitable and Inclusive Classrooms* by Amy J. Samuels (2018)

- Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students by Zaeretta Hammond (Book)

Participatory Learning (Hands-on Inquiry)

- Creating Contextually Authentic Science in a "Low-Performing" Urban Elementary School* by Cory A. Buxton (2005)

- Transforming Schooling through Technology: Twenty-First-Century Approaches to Participatory Learning* by Craig A. Cunningham (2009)

- Assessing Equity Beyond Knowledge- and Skills-based Outcomes: A Comparative Ethnography of Two Fourth-grade Reform-based Science Classrooms* by Heidi B. Carlone, Julie Haun-Frank, and Angela Webb (2011)

- "Chapter 3: Toward More Equitable Learning in Science" from the book, Helping Students Make Sense of the World using Next Generation Science & Engineering Practices, by Megan Bang, Bryan Brown, Angela Calabrese Barton, and others in association with NSTA.

More About the CRRSAA, CARES Act, and ARPA Funding

Since March 2020, the U.S. Department of Education has made more than $170 billion in stimulus funds available to schools, colleges, and universities. Provided through the CARES, CRRSA, and American Rescue Acts, these funds can be applied to a wide range of resources, including PPE, educational technology, summer and afterschool programs, and other allowable uses as outlined within the CRRSA, CARES, or American Rescue Plan Acts.

- The CARES Act, passed in March 2020, made stimulus funding available to K–12 schools and districts through two funds: the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) fund and the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief (GEER) fund.

- The CRRSA Act, passed in December 2020, made stimulus funding available for K–12 schools and districts through two funds: the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER II) fund and the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief (GEER II) fund.

- The American Rescue Plan Act, passed in March 2021, provided additional ESSER funding, known as the ESSER III fund. The ESSER III funding came with new requirements, including:

-

The SEAs must reserve allocations for the following applications: 5% to address learning loss, 1% for afterschool activities, and 1% for summer learning programs.

-

The LEAs must reserve at least 20% of the funding they receive to address learning loss.

-

Two-thirds of ESSER funds are immediately available to states. The remaining funds will be made available following states’ submissions of their ESSER implementation plans.

-