Does the Fizz from Pop Rocks Result from a Physical or Chemical Change?

Laura Celik shares her secret for helping middle schoolers investigate physical and chemical changes – Pop Rocks!

Physical and chemical changes are studied in both middle school physical science and high school chemistry classes. When investigating these topics, one commonly cited piece of evidence for a chemical change is the formation of a gas where there was none before, but the sudden appearance of gas bubbles can also be the result of a physical change.

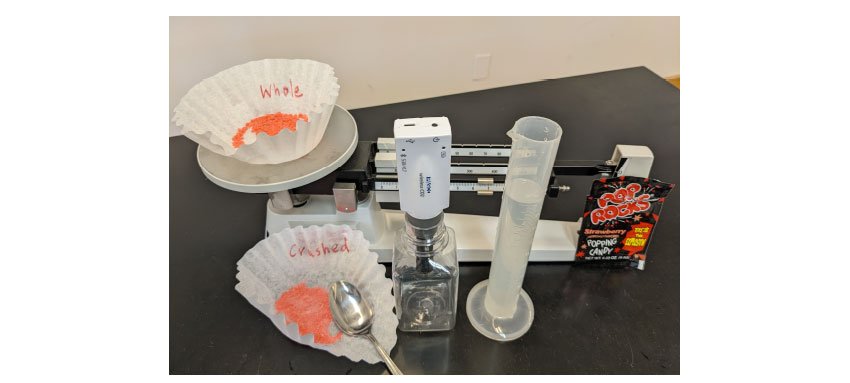

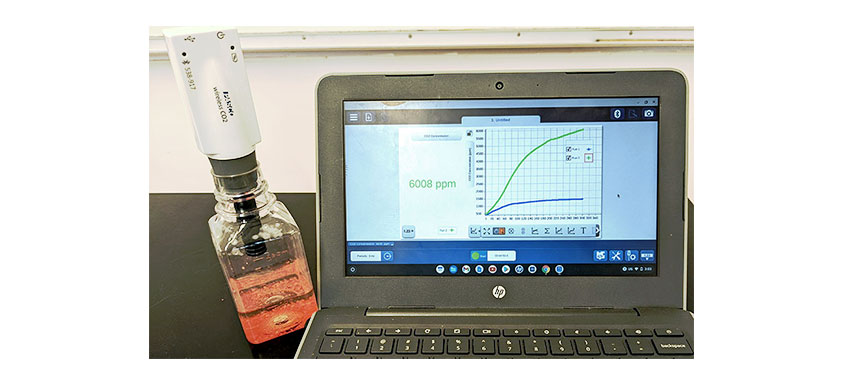

In this laboratory investigation, students are asked to predict whether the carbon dioxide bubbles that form when Pop Rocks are added to water are the product of a chemical reaction or the result of a physical change. Students begin by creating two equal mass samples of Pop Rocks, one crushed and one whole. They then add these Pop Rocks to water and record the resulting carbon dioxide concentration over time.

During the experiment, students find that adding crushed Pop Rocks to water results in significantly less carbon dioxide (about 4 times less) than adding whole Pop Rocks to water. They also notice that crushing the Pop Rocks creates a snapping, popping sound.

Students conclude that the carbon dioxide exists in the candy before water is added and that crushing the candy allows this carbon dioxide to escape. Carbon dioxide does not form in a chemical reaction with water but exists inside the candy all along. The bubbles form as the candy dissolves, which is a physical change.

Materials for Each Group

- Wireless CO2 Sensor

- Chromebook

- Triple beam balance or digital scale

- Water

- 1 packet of Pop Rocks

- 1 bottle

- 2 coffee filters

- 1 metal tablespoon

- 100 mL graduated cylinder

Teacher Tips

- Smaller groups of 2-4 students work best for this experiment.

- Encourage students to fully crush the Pop Rocks until they turn into a powder.

- Remind students not to shake or swirl the bottle, because the carbon dioxide sensor must stay dry.

Fun Media to Share with Students

This episode of Unwrapped from the Food Network, called "The Secret Way Pop Rocks Are Made" provides great context for the experiment.

Thank you to Laura Celik of Princeton Charter School, Princeton, NJ, for sharing this incredible lab! Download Laura's experiment below for complete instructions and student questions.

File Attachments

| Middle School Pop Rocks Lab – Physical or Chemical Change | File Size: 22.12 KB |